Source Latino | Interview With ‘Shadowshaper’ Author, Daniel José Older

Latino author Daniel José Older explains how his fiction stories are politically, culturally, and socially relevant to our word today.

Daniel José Older, holding a white Styrofoam cup in one hand and a blue cell-phone in the other, sat in a dimly lit coffee shop in a corner of the coffee crave, aside two attractive but not culturally hip brunets on the tip of Canal St.

It was the kind of meeting neither here nor there; barely New York, but not quite New Jersey; where as our conversation was just like his novels, a passage of time and space while remaining an in between-er. Now in his private studio, sans coffee table, with my girlfriend on the side with a clear view of it all, this philosopher sat calmly, wearing an ivy cap hat with a flannel patterned button shirt underneath the greyish over top.

He greeted us with a warm smile, and an accent similar to Common (if Common were from Brooklyn), and a wide understanding on the book industry, and Latinos trying to get a piece of the scene.

Older has been working on a series that he now lives off of, and steadily fighting for more Latino representation in the industry. He was tired of all the limitations attached to his frequented award shows; he was angry that the industry was based on exclusionary thinking from one race’s perspective, that, for the most part, had not authentically documented his life, until just recently, when Tony Award winning actress Anika Noni Rose announced that she and her production company, Roaring Virgin Productions, would option the TV/film rights to Older’s Bone Street Rumba urban fantasy series, published by Penguin’s Roc Books.

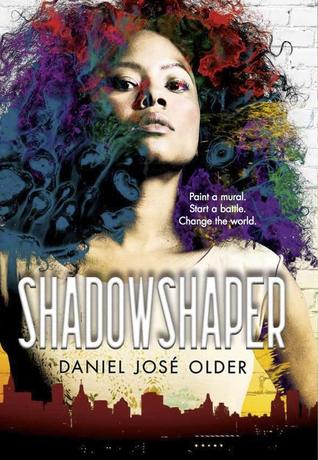

Older, an open advocate for Latinos in the entertainment field, titled his latest novel, Shadowshaper. Shadowshaper follows Sierra, a young woman living in the middle of a gentrified Brooklyn, who, once again, is neither belonging, but not quite an outsider, given her history in the borough and connection to its spirit. Older discovers a supernatural order called the Shadowshapers, who connect with spirits through paintings, music, and stories. Her grandfather once shared the order’s secrets with an anthropologist, Dr. Jonathan Wick, who turned the Caribbean magic to his own foul ends. Now, Wick attempts to become the ultimate Shadowshaper by killing all the others, one by one. With the help of her friends and the hot graffiti artist Robbie, Sierra must dodge Wick’s supernatural creations, harness her own Shadowshaping abilities, and save her family’s past, present, and future.

Older, an open advocate for Latinos in the entertainment field, titled his latest novel, Shadowshaper. Shadowshaper follows Sierra, a young woman living in the middle of a gentrified Brooklyn, who, once again, is neither belonging, but not quite an outsider, given her history in the borough and connection to its spirit. Older discovers a supernatural order called the Shadowshapers, who connect with spirits through paintings, music, and stories. Her grandfather once shared the order’s secrets with an anthropologist, Dr. Jonathan Wick, who turned the Caribbean magic to his own foul ends. Now, Wick attempts to become the ultimate Shadowshaper by killing all the others, one by one. With the help of her friends and the hot graffiti artist Robbie, Sierra must dodge Wick’s supernatural creations, harness her own Shadowshaping abilities, and save her family’s past, present, and future.

We sat down with Older to speak on how his philosophy and way of thinking lived within Shadowshaper.

The Source: In your writing, you explore various themes and use ghost stories to address serious issues of today like gentrification, cultural appropriation, surviving trauma, and falling in love—territory that traditional ghost stories don’t often venture into. How have these crises influenced your work, now, and moving forward?

I think there’s been a lot. Hmmm, let me think. Well, certainly we’ve been talking about crisis the whole time. They’ll tell you conflict is the music of story, and historically we look at these moments of crisis. I think the exciting thing about crisis is when mythology has been broken open. I’m always talking about how we need new mythology, and we do have it–we just have to switch the paradigm of who is telling and distributing these stories. making it a form of crisis and accepting it as a form of crisis is the key to change. The problem usually is–well you own the world, and that’s how it is! But no, its very dehumanizing–these structures become dehumanized. White people in this country have become dehumanized as the benefactors of white privilege. We don’t talk about racism being a problem of white people. but this goes back to Sierra, and how this is a world of crisis; internally, and externally, and how we survive.

The Source: From what I’ve read, I understood the book to have common themes of reinvention and reconciliation of ones’ past and ones’ identity – what is your story as a writer?

I believe a month after I quit (my ambulance job) that’s when the publishing deal came, and it didn’t come easy! I had been writing since 2009. I have been a full time writer for two years now. I was a paramedic for ten. I feel like when you commit to something and that’s YOUR path and you believe in it, and you make a move with it–that’s when it happens.

The Source: You’ve mentioned community is a vital aspect in your goal as a writer, both a domestic one and creative one; you’ve always said community is a way of survival. Elaborate, please.

I think survivors are, to me, surviving on the strength on community, and I guess my characters don’t do it that well, because there’s a lot of conflict within the communities. As you see, the characters have been erased of their identities–as they became in-betweeners, or people walking the fine line of life and death, they are more or less straddlers–they don’t have IDs, they don’t have credit cards, and the only way they can survive is by coming together. They don’t like each other, but they find some sense of community and band together on that strength. To me, that is the ultimate truth.

The Source: Do you think all authors write out of having a particular need? What is your need? In the past, you called it an urgency; what exactly is this urgency?

We have to shut down entire cities to say black lives matter. Literature and stories are always a part of struggle. As Deray Mckesson has said, ‘At the heart of every revolution is a well-told story.’ We don’t block traffic because we want to; it’s because we have to. That’s why I write, to enhance life. Seeing and living in this world, and that’s the urgency; living through life and death. People aren’t dying faster than they were before; we’re just paying attention…just as gentrification is not a new phenomenon, and it may take decades; but people are and always have been displaced. Reading the urgency of other writers inspires my own urgency.

The Source: In the past you’ve written, “There is always a moment of absolute crisis at the pinnacle of every great change.” You’ve created a world in your novels you know exists, but at this “mortal” point in your life cannot access, except via this dialogue you’ve created. How has writing these books freed you and your need to express your ideologies?

That’s literally why I write; that’s what makes a story dynamic to me, that’s what makes good literature. Themes of power, race, and indifference are layers of a problem, and that’s what makes a great story: a difficult story, unfolding what needs to be discussed. My novels are forms of truth that doesn’t make you comfortable. To add to that, in Shadowshaper, Sierra is moving through Brooklyn as a teenager, and she has a very emotional conversation and connection with Brooklyn–and although shes moving through this gentrified area, having to move is a very emotional thing–so for Sierra, having memories of the street corner where her best friends played hopscotch, and where her best friends were killed in her neighborhood, it affects her heavily, due to the social change she feels. She feels like a stranger in her own home and body. She’s kind of like ‘Why am I a stranger in my own neighborhood?’ until she realizes she is a stranger in her own neighborhood. And that’s the world moving passed her. That’s another story in itself. That’s a story I relate too very much.

Western culture is so negative towards ghosts. I wanted a character that could relate to spirit. So Sierra is freaked out, but she also gets used to it. That’s because she was born in a Latino family, where spirits are normal. I wanted to get over that ‘OMG, ghosts’ and just wanted to deal with spirits, deal with death, and continue to move forward.

As a paramedic, I was struggling to become an artist and find a voice. Sierra is a muralist where she combines art and spirits and communes herself. I don’t see this in our movies; usually ghosts are just trying to kill us, when ghosts are just complex as humans. I believe there’s power of the mind where we don’t tap into, except through meditation, through prayer. I am a spiritual man. and the writing is physicalizing prayer. when I walk through Brooklyn streets I pray–because, what is prayer? Intention, right? My characters embody and physicalize prayer and push that forward; just like myself. In writing these stories, I became the writer I needed to be in order to write them.

– Hurtjohn

Featured image photo credit: Ashley Ford