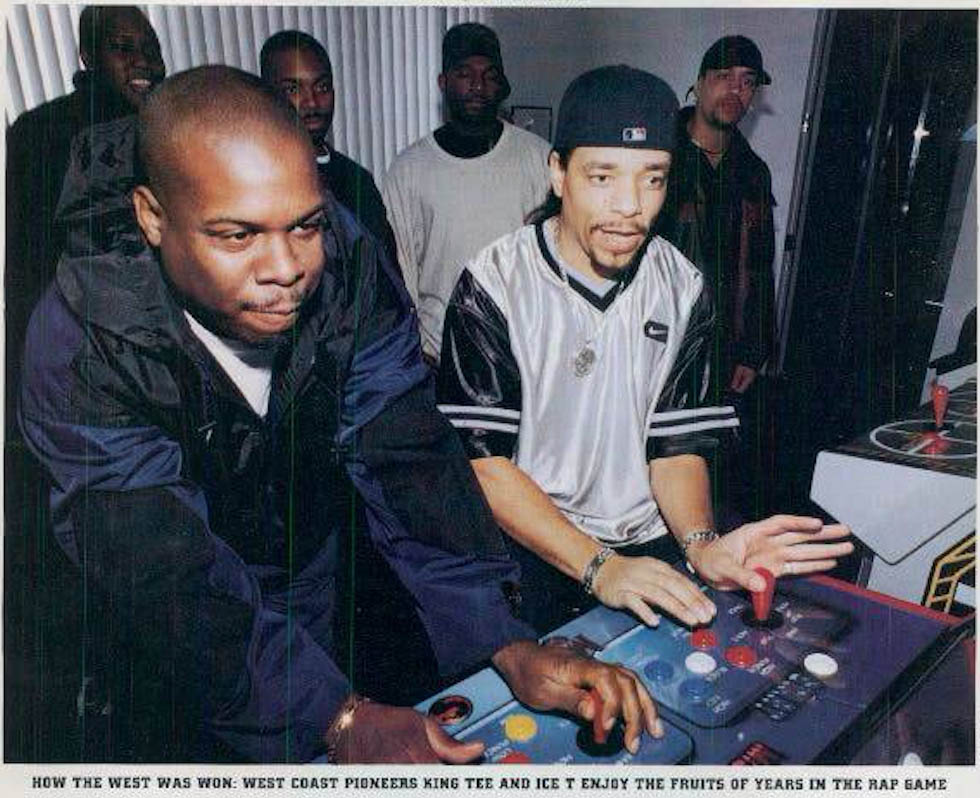

The Source |BANGIN': For Life, Love & a Future – Ice-T relives his gangsta days

Words by Sia Michel

This article was originally published in The Source Magazine, April 1996 (Issue #79)

BANGIN’: For Life, Love & A Future

Ice-T relives his gangsta days and looks into the future of peace in the war-torn street zones of the ‘hood’

Ice-T has invaded the White House. A long spiraling road takes you to his proverbial house on the hill, past Tider estates and Spanish missions, Greek temples and swinging ’70s bachelor play pens. Ice-T resides at the very top, in a modern ivory mansion that hangs precociously down a giant cliff, in defiance of everyday L.A. horrors like earthquakes and mudslides. On one side, wall-sized windows promise spectacular views of Hollywood and beyond; on the other, snarling guard dogs keep watch. Beemers and Benzes line the street in front of the house, their insides hidden by smoked glass.

A handwritten sign on the front door reads, “Don’t ring the doorbell. Use the side entrance!” We can’t figure out how to get in. The only other door leads to the garage, and when we climb a set of stairs that lead mysteriously to the roof, the pittbulls go crazy, like they’re about to jump the fence and rip us to shreds. We’re not stupid enough to hit the front buzzer and piss off Ice-T, but we are stupid enough to climb through an addition to the house still under construction, weaving carefully through tools and cements bags. Next we fell into the crater that will one day be an enormous swimming pool.

Suddenly we’re looking right through a glass door into Ice’s TV room. “Who the f*ck is that?” He yells in alarm. As images of that much-rumored arsenal in Ice’s basement comes to mind, we start shouting our names in our most innocent girly voices. Finally, Ice’s wife Darlene lets us in. Suffice to say, security is going to be beefed up at the T residence.

Inside, Ice-T— the touted inventor of gangsta rap. The former gang member who once threatened to sick 150,000 Crips and Bloods on the LAPD, the rapper who brought us “Cop Killer” and “Let’s Get Butt Naked and F***”—is sitting on the couch eating his meat and potatoes off of a blue plastic TV tray. As he tunes into the American Music Awards in his big-screen television, his cute-as-a-button four-year-old son giggles beside him. Meanwhile, Darlene washes dishes in the adjoining kitchen, her infamous assets threatening to bust out of a dress that’s one inch of fabric away from a bathing suit. It’s an only slightly of killer scene of domestic bliss, a symbol of the kind of family life that eluded Ice-T for most of his life.

His parents were killed in a car accident when he was still a shorty. He had no brothers or sisters. His only living relative was an aunt who moved him from Newark to L.A.; she died not long after. “I was living in the ghetto with no back-up.” Ice-T says. “No real friends.” Like many kids who felt adrift in the inner-city, he was lured into gang life by the promise of an immediate circle of friends, protection, status, a code of rules by which to navigate the bedlam of the streets, not to mention the chance to make bank. Feeling especially ostracized, he says, because he was”yellow.” He was determined to get a rep. He became a Crip.

“I was the one who would go into the party and it’d be a perfectly cool one, and I’d just be wanting to knock over people’s aquariums and be out in front shooting,” Ice-T explains. “I just wanted to be known.” That is, to become notorious, his very presence a threat that sh*t was gonna go down. But more than anything, Ice was looking for a surrogate family.

“It was the first place I had somebody tell me the word love,” he says. “I had never really been around a parent who was willing to say he loved me. Now, my kid, I tell him I love him everyday. But there was none of that love, love, love stuff then. Like I wrote in The Ice Opinion, it’s like male love pushed to the pinnacle. When you get into a gang, maybe I’d look at you, and say, ‘We’re down with this ‘hood, and no matter what happens, nothing will ever happen to you…homey. I mean it, and if something does happen, we will retaliate.”

Ice-T’s house is flat-out bella: black leather furniture, black shag carpets, gold records hanging on the walls. When an impressed reporter once asked him where he found his decorator, Ice-T replied, “I done broke into houses to know what kind of sh*t I wanted when I got a f*ckin’ house.” He leads us down into his newly built home studio. Framed pictures of lynched black men int the hallway walls. In one, a hanged man is surrounded by a crowd of laughing, jeering spectators, some of them carrying picnic baskets. Another photo captures the death threats of a bound and torched victim, his face a mask of agony. The studio decor is no less confrontational: there’s an enormous aquarium filled with a stingray and miniature sharks.

“Watch this,” Ice-T says. He turns down the lights until the equipment fades away. “Now look out the window. You’re looking right over the cliff, like you’re floating in space and sh*t.”

He looks exhausted. Earlier today, he flew back from Mexico, where he was recording songs from the upcoming, Body Count album, Violent Demise, then immediately started re-mastering songs for his new solo record, Ice-T 8: Return of the Real. While most rappers are lucky if they make it to their third album these days, Ice-T has been in the game for a decade, always a visible presence even if his records weren’t platinum sellers.

In addition to a prolific film career, which includes starring roles in action films like New Jack City, Ricochet, Surviving the Game, Ice-T found himself a poster boy for free speech during the “Cop Killer” controversy, penned a book called The Ice Opinion, and hit the campus lecture circuit. Now he’s even got his own TV show, Players, on NBC, about “criminals picked up by the government to fight crime with crime.” Ice compares it to The Sting, Charlie’s Angels, Mission Impossible and Miami Vice rolled into one. Would you expect anything less from a fan of Iceberg Slim?

“My motto,” Ice says, “is I’m not turning down anything by my collar—and I’m keepin’ that up too.”

Despite his O.G. Image, Ice-T can be disarmingly friendly in person. Definitely not soft, but down-to-earth. He speaks plainly and directly, with the common sense of someone who’s seen it all, digested it and remained hyper-observant. A clear sense of right and wrong has been integral to his art since the blood-spattered, gun-crazy fables on his second album, Power, Ice has got an opinion about everything as his book title suggests, and he’ll lay it out in long paragraphs.

Ice-T’s persona is a collage of paradoxes: the body-crazed pimp daddy who’s stood by the same woman for 10 years, the high-rollin’ hustle who spins moralistic tales of the ‘hood, the gangbanger who tries to increase the peace, the Black militants who comes off color blind, the gangsta rapper who plays to white kids in a heavy metal band, the rich man in the hills with one foot in the streets. His sheer charisma has always been one of his biggest assets, taking over when maybe his beats were a little flat, his acting a little raw. Ice-T once described himself as the “ghetto friend that kids can talk to.” Black, white whatever. Today, he boasts of “diplomatic immunity.

“I think I get respect because I won’t talk about things I haven’t been through to some extent,” Ice says. “That’s why I don’t try to get up here to tell you I’m the supernatural gangbanger of L.A. ’cause I’ma have to go back these streets, and homey be like, “Yo, Ice-T ain’t killed 25 men.”

“Now, I was never really a hardcore member of the Crips. I never actually went out and did drive-bys, or put in work on nobody but if you went to Crenshaw High School, you was Cripping and that’s just point blank. It was pretty much being run by Crips, and there was no way you could really go to that school without being affiliated with the gang. You kind of had to be down or you’d be an outcast and victimized by other people. But it was cool… It’s important to remember that the gangs weren’t so violent at that time. Now the gangs are extremely violent.”

Ice-T’s experience captures the reality of gang life behind the media hype. Despite the hyper-violent image of the typical gang member, the actually number of hardcore gangbangers—those who actually kill for their colors—is only a small percentage of the gang population as a whole. Most of the kids are in just to kick it, learn the lingo, maybe sell some rock or pull the occasional heist, impress the girls. Ice-T wasn’t in deep enough to have much trouble facing out. When he got his Hoover Criplette girlfriend pregnant, he knew his 3 1/2 year stint was over. Ice-T calls gangs “microcosms of the crazy macho war sh*t that rules the world.” Gang members do learn to love something and risk their lives for an ideal, he says, but those positive qualities are misdirected—they’re venting their frustration against their own people rather than the authority figures keeping everybody down.

“They say god looks after fools and children,” Ice-T says, “and at the time, I wasn’t really aware that some of the stuff we did was causing so much pain to people. Therefore, I think I got a pass. Now when I look back on it. Some of the sh*t I did was foul, but most of it was just based on survival or not knowing. I don’t regret nothing, but I try to make up for some of the sh*t I did by informing other people about it in my music, just trying to tell kids the right thing to do.”

Then again, Ice-T once showed up on the Arsenio Hall show with a blue rag on his head—in the middle of the Crips/Bloods gang truce he was supposedly helping to promote. “Folks was like, ‘Why’d you do that?’ I’m like, ‘Yo homey, they was my people and I wanted to let people know that I wasn’t hiding from the issue. I’m going to put myself right out. This is who I am, but I still want the peace.” Still, doesn’t Ice-T fear that such inflammatory behavior, coming from someone like him, inadvertently glamorizes gang life even as he criticizes it?

“I don’t have no fear of using the word ‘cuz,” he says, ” ’cause I was affiliated with the Crips. I’m not trying to promote ’em though. That’s who I was.” For that reason, Ice says he doesn’t discredit industry players—like Death Row CEO Surge Knight, a Blood, who publicly maintain their gang allegiances. “If that’s what he is and he wants to represent himself,” Ice-T says, clapping his hands together for emphasis, “that’s him, you know what I’m saying?”

“Once you’ve been involved with gangs, it’s for life. It’s not like something you can totally ever really get away from. People die. It’s not like a club; thousand of people have died on each side of the gang scene, so it’s more real than you can possibly imagine. You might never have been in a gang but if you learned that some Crips killed your sister and I was a Crip, you’d definitely have a feeling about me, whether or not I was involved. And when you got groups of men who not only endure murder, but murder together in retaliation, then you’ve got a bond for life. The ability to turn on your color is really hard. You can embrace the other color, that’s peace, but you got to represent what you are because your boys died for that. It’s as real as any war.”

After the L.A. uprising of 1992, as burnt-down buildings still smoldered and families buried their dead, a group of young gangbangers from Watts, finally sickened by the violence, set out to orchestrate a ceasefire. An ex-gang member named Anthony Perry modeled the blueprint for a truce after an Egypt/Israeli treaty written by a Black diplomat from Watts named Ralph Bunche, who won the Nobel Prize in 1950. Soon, Tony Bogard, an infamous Crip, and Tyrone Baker, a Blood, started the non-profit group, Hands Across Watts. Similar organizations like South Central Blackness, Yes I can and Phase Two also sprang phoenix-like from the ashes. After decades of war, Bloods and Crips were tying their bandannas together.

Ice-T heard about the truce while he was on the road. “I couldn’t believe it,” he says. “I had wanted a truce for a long time, even rapped about it in the song ‘Colors’ and sh*t.” He dashed out a song called “Got a Lotta Love” on the tour bus, and promised to donate all the profits to Hands Across Watts. After a buddy from his crime days introduced him to Bogard and Thai Stick, a well-known Bountyhunter (a Blood set), Ice was convinced to join the board of directors. The problem was, despite all the lip service politicians and celebrities paid to rebuilding inner-city L.A., there was no cash coming in. “No one would give us a dime,” Ice says. “No record labels, no one. It was a wound that no one aired to heal. The attitude was like, ‘Gangbangers? Send ’em off to jail.”

Then, 10 months into the truce, Tony Bogard was murdered. He was shot while confronting a drug dealer in his neighborhood. “That was really dramatic to me,” Ice says, “to see someone who went from negative to positive get killed. I went out there with my own money and spent close to $200,000 but there was no other aid.”

Though most of the peace organizations dissolved for lack of finances, the legacy of the truce lives on. Gang-related homicides decreased drastically; in some neighborhood, they were down 48 percent. And in ensuing years, other young activists grouped together to promote intra-gang peace. If some of L.A.’s estimated 400 sets are still at war, things have definitely chilled.

“The vibe isn’t as negative as it was,” Ice agrees. “you can go to concerts now and there’ll be lots of different gang members, but they won’t set trip as easily. There’s usually someone going, ‘No, no, no. Keep it cool.’ But in the old days, it would be n as soon as the other color was in sight. Now they won’t gangbang unless it’s provoked.”

“As far as a forever truce, this might sound corny, but you gotta give kids something else to do,” he continues. “You gotta reinstate hope and give them something they feel is worth living for. ‘Cause the whole street mentality is like, ‘F*ck it. I’m gonna die anyway, and I don’t got nothing really going.’ You don’t see kids dropping out of law school and stealing cars. You don’t do that when you see a horizon ahead. If you check into the Nazi of skinhead gangs, it’s white kids who just feel like there’s no hope.”

The first thing we need to do, Ice thinks, is to concentrate on the elementary schools, and hire gang counselors to sniff out the first sign of trouble. He says that current gangbangers are so brainwashed that the only things that will snap them out of it is a death really close to them or moving away. Some of his other solutions—restructuring society so that teaching is the highest paid profession (more than police work, anyway) guaranteeing a free college education to everyone—seem like pie-in-the-sky for a notion under the next government. But his main hope—that gangs will eventually clear themselves out and become as unhip as once cool cracksmoking has—is a distinct possibility.

“Gang membership will change,” he stresses. “Right now, it’s kinda uncool in L.A. to set trip. It’ll have to be uncool to kill another Black man. Otherwise, to paraphrase a Crips slogan, gangss won’t die, they’ll multiply.

There’s an old Sicilian saying that, ‘Man is the only animal that will dine with the enemies.’ Ice-T’s freedom-fighter image took a credibility hit when he gave Time Warner the go-ahead to delete “Cop Killer” from future pressings of Body Count; worse yet, he helped create the history that was doomed to repeat itself. In part because he and Time Warner curbed in to Dan Quayle’s “morality” police four years ago, rap music was an obvious target when the next election year rolled around.

Ice-T says that he realized he had his own “family values” to consider once the shakedown got really bad—his daughter got pulled out of school and questioned by the feds, Darlene was scared, and he was audited three times. “That ‘Cop Killer’ sh*t was an early warning signal that you can’t be connected to a major corporation and speak out against the government at the same time,” he argues. He released the angry, issues-oriented Home Invasion and his own Rhyme Syndicate label in 1993.

Today, he wants to move away from his spokesman image. “When you start rapping on the streets, you rap about what matters to you. Then you get some power, and people are like, ‘his voice drops to a whisper,’ ‘Yo, rap about AIDS.’ Then you go get out and learn about it and then you rap about AIDS. A lop of people will forget what you care about, I want to help everybody. But after a while, it does become a burden, like you can’t be a person anymore. I wanted to say what I really wanted to on this album and make records for my homeboys.”

If Home Invasion is political, this sh*t is like [the movie] Casino,” he laughs. The 24-song Return of the Real is split into a hardcore “G” (gangsta) side and a laid-back “P” (playaz) side, and, in a new move for Ice-T, includes some laid-back radio-ready singles. Even so, the message is his medium. There are several gang-oriented morality tales, such as “Dear Honey” in which a dead Crip testifies from the grave. “I told you, gangbanging ain’t no joke.”

Ice-T can’t help preaching, trying to convince kids that the disease can be cured, that they’ve got a chance to make a better life if they think straight and put their minds to it. “The reason I live here to this day is that I hated the ghetto so much, all the violence there, that I busted my ass to get out. People always come up and say, ‘Ice, why you live on the hill?’and I say, ‘Look, everyone in the ghetto wants to live in the hills—no one lives there ‘cause they want to. Why do you think they’re stealing and robbing banks? They’re trying to have a better life.” With that, he escorts us out of the house, past the Samurai statues and the lynching photos, past the gold plaques and sting rays, past his wife and son half asleep in the couch. Away from… his new family.